“What’s his name again, Mum?”

My four-year-old son was looking at his father, the man who had tucked him into bed every night of his life, and he couldn’t say the word “Dad.”

It had started seemingly overnight.

Words that began with ‘t’ or ‘d’ became impossible for him. He couldn’t say “dinosaur”—his absolute favourite thing in the world. He couldn’t say his own name.

This brilliant little boy, who had been chattering away just days before, was suddenly stuttering and stammering on sounds he’d never struggled with. But this felt like more than a speech issue. His jaw would clench as he tried to get the words out, and then he started finding creative workarounds to avoid the words that now trapped his tongue.

When his father walked into the room, instead of his usual excited “Daddy, look at this!” we’d hear that heartbreaking question, “What’s his name again, Mum?” as he’d get me to say “Dad” so he could then finish his sentence.

I remember the exact moment it hit me how much he was struggling. My husband and I exchanged glances across the kitchen table, and I saw my own fear reflected in his eyes.

Something was happening to our son, and we had no idea what.

The nights that followed were filled with whispered conversations after bedtime, frantic Google searches, and that particular kind of parental terror that sits heavy in your chest, the kind that feels suffocating.

We went to our doctor first, worried about neurological problems. Could something be affecting his development? Some kind of processing disorder? The doctor gave us the all-clear physically, but we were no closer to answers.

Our naturopath ruled out nutritional deficiencies and then gently suggested something I’d never heard of: that our son might be highly sensitive. She recommended a counsellor trained in Dr. Gordon Neufeld’s work. And slowly, piece by piece, we began to understand what was happening.

Our son’s nervous system was wired to process the world more deeply and intensely than other children. And in hindsight, the weeks leading up to his speech struggles, his world had become very, very full. To the point of overwhelm.

We’d been on vacation. His dad had been traveling for work more than usual. We’d had family visiting. We’d been dipping our toes into forest school.

There had been significant changes to his routine, new experiences, and layers of stimulation that his little nervous system had been working overtime to process. Like a computer with too many programs running, something had to shut down.

So, I took two weeks off work immediately. We cancelled everything—playdates, forest school, appointments, commitments. We stripped his world back to just what his nervous system needed: calm mornings, abundant play, deep connection, and predictable rhythms.

I’d always embraced simplicity in our parenting, influenced by Kim John Payne’s work. But now I really leaned into it—more nature, more unstructured time, more presence. Less noise, fewer demands, gentler rhythms.

Within days, the “t” and “d” words started coming back.

Within two weeks, his spark returned.

But more importantly, I could finally see my son clearly for the first time.

He had always been what I now know to as an orchid child, or a highly sensitive or deeply feeling kid.

He’d been a velcro, koala baby, happiest when held close, sleeping best when he could feel my heartbeat, crying when strangers tried to hold him. But when he was in the right environment—on me—he was such a happy baby. He’d make eye contact with strangers when he was just weeks old, smiling and giggling, absolutely thriving, just like orchids do when they get exactly what they need.

I remember as I sat with this new understanding, feeling a mixture of relief and overwhelm. Relief that there was nothing “wrong” with my son, but overwhelm at realising how much more intentional I needed to be in my parenting and about the world we were creating for him.

But I also felt profoundly grateful that we had followed a responsive, attachment-focused approach from the very beginning. We’d never used sleep training or traditional discipline techniques—he didn’t know what a time out was or what a “consequence” meant. I don’t believe that way of parenting is right for any child, but for a highly sensitive child, it would be crushing.

So, let’s dive into what it means to have a highly sensitive child—not just the scientific explanation, but what it actually looks like when you’re raising one of these remarkable children.

What Does It Really Mean to Be Highly Sensitive?

Here’s what I wish someone had told me earlier: about 30% of the population has what scientists call sensory processing sensitivity. It’s not a disorder or something that needs fixing. It’s a temperament trait that’s been observed in over 100 species—a different way of experiencing and processing the world.

From an evolutionary perspective, these were the people who could smell smoke before anyone else noticed the fire. They sensed danger when others felt safe. They were the early warning system that helped keep the entire tribe alive.

Dr. Thomas Boyce, who spent decades studying highly sensitive children, uses a beautiful metaphor to explain this difference. He calls highly sensitive children “orchids” and their less sensitive peers “dandelions.”

Picture a dandelion. Resilient. Adaptable. It grows in cracks in the sidewalk, survives drought, thrives in poor soil. You can forget to water it, leave it in blazing sun or deep shade—doesn’t matter. That dandelion will find a way to flourish.

Now picture an orchid. Exquisite. Delicate. It needs just the right amount of humidity, the perfect balance of light and shadow, water that’s neither too much nor too little. Get those conditions wrong, and the orchid withers. But get them right? The orchid doesn’t just survive—it becomes the most beautiful flower you’ve ever seen.

Highly sensitive children are orchids.

When I first heard this metaphor, everything clicked.

The environment we create for these children doesn’t just matter—it determines whether they struggle or soar. So, suddenly, my son’s meltdowns after full on days, his need for “extra” comfort, his intense reactions to seemingly small things—it all made sense.

Research backs this up in ways that should give every parent of a sensitive child hope.

Studies show that in harsh or unsupportive environments, highly sensitive children do indeed struggle more than their peers—more anxiety, more depression, more difficulties navigating the world.

But in nurturing, responsive environments, something remarkable happens. They don’t just catch up to their less sensitive peers—they often surpass them in emotional wellbeing, creativity, social skills, and even academic achievement.

This means that the choices we make as parents of a highly sensitive child and the environment we provide for them—and I won’t sugarcoat this—matters more. The stakes feel higher simply because they are. But so are the potential rewards.

Your highly sensitive child isn’t harder to raise because something’s wrong with them. They’re simply more affected by their physical and emotional environment because that’s exactly how they’re designed to be.

In many ways, these children are wired for the kind of childhood all children were actually meant to have—slow rhythms, simple pleasures, abundant free play, and deep connection with their families. They thrive with time and space to just be children. But our modern world has created a pressure cooker of overscheduling, too much stuff, too much stimulation, and too little downtime.

While all kids can suffer under these conditions, our highly sensitive children are the canaries in the coal mine, cracking under pressure others might endure.

This makes it even more crucial for parents of sensitive children to become fierce advocates for a different way of living. We need to say no to the cultural pressures that demand our children grow up too fast, do too much, and have too much. Our orchid children are showing us what childhood was always meant to look like.

What This Actually Looks Like When You’re Living It

Let’s forget the textbook descriptions for a moment and let me paint you a picture of what sensitivity actually looks like in your everyday life.

Picture the child who notices everything. While other kids are playing happily at the playground, your highly sensitive child spots the mum across the park who looks sad and asks you, “Why is that lady crying?” They notice immediately when you’ve rearranged the furniture, even if you’ve only moved a chair six inches. They can tell their teacher is having a rough day before she’s even spoken a word. They’re the ones who remember exactly where every toy should go in the gift shop and feel compelled to tidy up what other children have scattered.

Picture the child whose emotions run deeper than an ocean. When you’re feeling sad or overwhelmed, they feel it too—not just noticing it, but absorbing your emotion into their own small body. They’ll come over and try to console you in the sweetest of ways that few adults ever have, patting your back or bringing you their favourite stuffed animal because they genuinely cannot bear to see you hurting. They’re inconsolable when the family dog in their favourite movie gets lost and a friend choosing to play with someone else at recess doesn’t just disappoint them—it feels like genuine rejection that they’ll carry in their hearts for days, if not weeks.

When your voice rises slightly in frustration about the morning rush, they look at you with wounded eyes asking, “Why are you yelling at me, Mama?” What seems like a normal tone to you feels harsh and overwhelming to their sensitive nervous system.

Picture the child who needs time to understand their world before diving in. They’re not being shy when they cling to your leg at the birthday party—they’re carefully observing. Cautious. They’re asking, who are these children? How do they play? Does this feel safe? They might spend the first half hour of any new experience watching, gathering crucial information about whether this environment feels safe enough to engage. Because when they do open up, you better believe their heart will be wide open—more vulnerable and tender than most, and it can be wounded more easily.

Picture the child for whom sounds feel amplified. They’re the ones you warn before you start the blender so they can cover their ears or go to another room. They leave when you vacuum and wear headphones at the movie theatre. These aren’t signs of weakness—they’re signs of a nervous system that processes sensory input more deeply, more intensely.

Picture the child who thrives on predictable rhythms and likes to know what’s coming next. Surprise changes to plans can feel genuinely overwhelming, not because they’re inflexible, but because their nervous system finds safety in knowing what to expect. They flourish when you tell them the plan for the day and give them gentle warnings about transitions.

Picture the child who seeks comfort in ways others might judge. They’re the four-year-old who wants to be nursed to sleep, the school-aged child who needs you to lay with them until they drift off, the teenager who still crawls into your bed when friend drama feels overwhelming. These aren’t signs of being “spoiled” or “coddled”—they’re signs of a nervous system that finds regulation through connection and struggles to settle without that safety.

After a day full of stimulation, they might have magnificent emotional releases—not tantrums, but their nervous system’s way of processing all the input they’ve been holding. They have trouble sleeping when their routine is disrupted or their mind is processing the day’s emotional experiences. They often prefer to play with one close friend rather than navigate the complexities of group dynamics. These children love to go deep, not wide, with their friendships—forming intense, meaningful bonds rather than having lots of different friends.

These children ask profound questions that catch you off guard. “Why do people hurt each other?” “What happens to animals when they die?” “Mummy, can you figure out how to live forever?” Their deep processing of the world around them leads to insights that seem beyond their years.

This doesn’t mean they’re fragile—far from it.

With the right conditions, they can be the happiest, most emotionally intelligent, empathetic, resilient, balanced children in the room. But we need to be paying attention for these kids. We need to be the protective barrier between our sensitive children and an often insensitive world, while also preparing them for it—building them up, helping them develop emotional skills, teaching them how to process their big feelings. It’s a LOT to be a parent of a deeply feeling child, I’m right there with you.

But, when you start to see your child through this lens—as someone whose nervous system is simply wired to experience life more intensely—everything shifts. What once felt like challenging behaviour becomes communication. What seemed like overreaction becomes deep feeling. What appeared to be clinginess becomes a wise beautiful need for connection.

Your child isn’t broken. They’re not too much. They’re exactly as they’re meant to be—feeling deeply, noticing keenly, loving fiercely. They just need a world that understands.

A quick note: While highly sensitive children and autistic children can share some traits around sensory processing, they’re distinctly different. Sensitivity is a temperament trait that occurs in about 30% of the population, while autism is a distinct neurotype that affects about 2% and involves core differences in social communication and interaction. Both are valuable forms of neurodiversity that deserve understanding and support. (1)

The Extraordinary Gifts Hidden in Plain Sight

Here’s what our culture gets devastatingly wrong. When we tell highly sensitive children to “toughen up” or “stop being so dramatic,” we’re asking them to dull the very qualities that make them extraordinary.

Their sensitivity isn’t a flaw to be fixed—it’s often the source of their greatest strengths.

These children, when supported rather than suppressed, become the adults who lead with exceptional empathy and emotional intelligence.

They create breathtaking art, music, and literature because they feel life so deeply.

They notice injustices others overlook and become fierce advocates for change.

They form relationships of unusual depth and meaning because they understand the human condition.

The very traits that might exhaust you as a parent—their intense emotions, their need for predictability, their careful observation of new situations—are actually preparing them to become thoughtful, perceptive, and deeply compassionate adults.

My son, the one who couldn’t say “dinosaur” that scary week when he was four? He’s now the child who notices when someone a friend looks sad and finds a way to help. He creates elaborate, imaginative stories that astound us, as parents. He remembers details from conversations we had months (or years) ago and brings them up at exactly the right moment to show he cares.

This is the gift of sensitivity, when it’s nurtured rather than suppressed.

Trust Yourself – You’ve Got This

As you navigate this journey of recognising and understanding your highly sensitive child, I want you to remember something crucial: you don’t need to be a perfect parent (there’s no such thing).

You don’t need to have all the answers. You need to BE their answer, as Dr. Gordon Neufeld teaches.

You need to deepen your intuition.

Develop your insight.

See your child clearly and trust what you observe.

When well-meaning family members suggest your child needs to “toughen up,” trust your instincts telling you they need understanding instead.

When teachers imply your child is “too sensitive,” trust your knowledge that their sensitivity is a strength, not a weakness.

When society pressures you to push your orchid child into environments that wither them, trust your protective instincts.

Your highly sensitive child didn’t choose you by accident. They need someone who will see past the challenging moments to the extraordinary human being underneath.

They need someone who will recognise their sensitivity as the gift it truly is. They need someone who will be their advocate in a world that doesn’t always understand.

That someone is you.

P.S. This topic of high sensitivity is huge…I’m coming back with part two of this post so stay tuned.

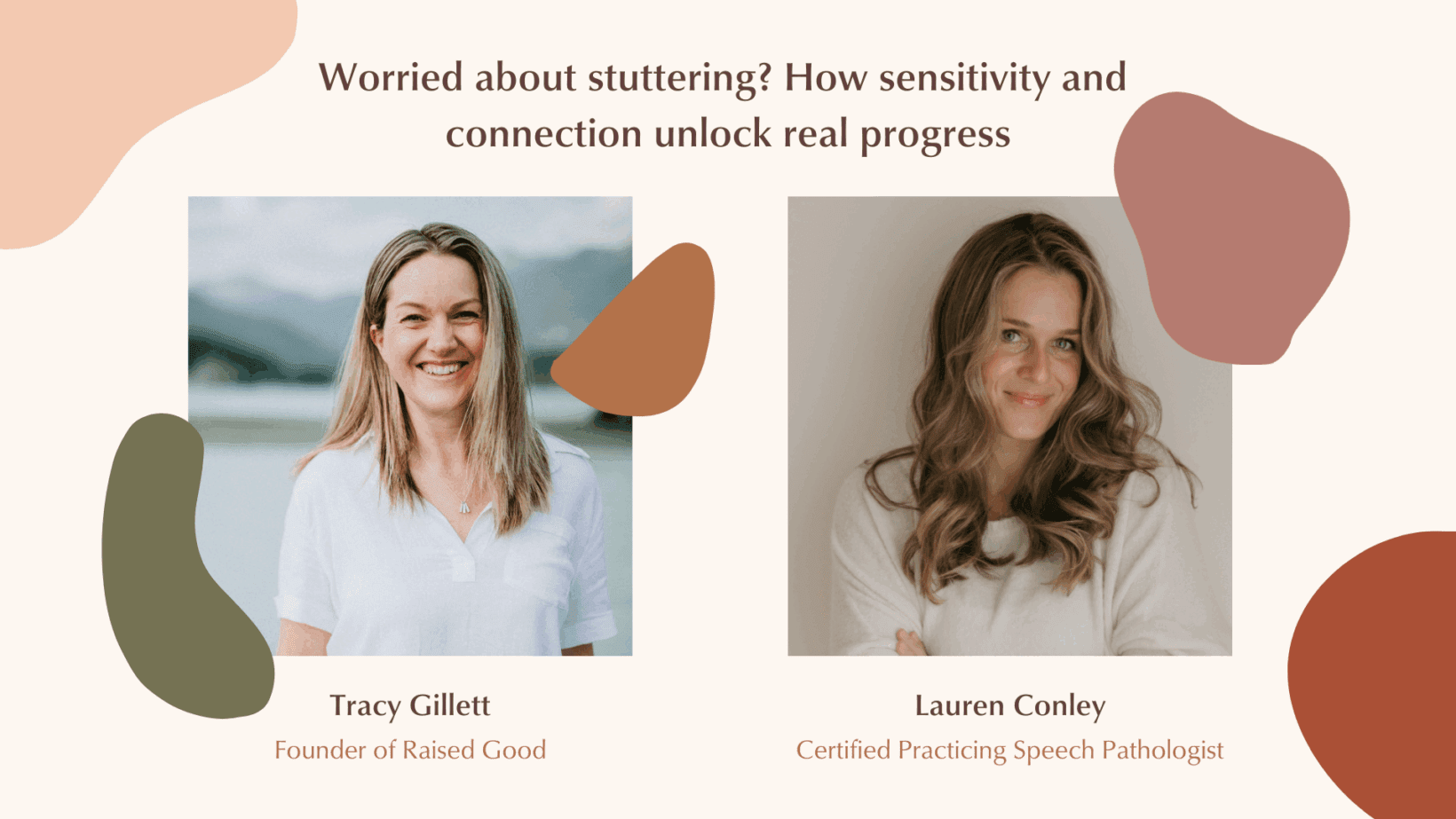

And if you’re wondering whether your child might be highly sensitive, or if you’ve just had that ‘aha moment’ of recognition, speech pathologist Lauren Conley’s masterclass at the upcoming Raised Good Online Summit on September 18th is perfect for you. Lauren discovered that over 84% of children who stutter have highly sensitive nervous systems – but her insights apply to ALL sensitive children, whether they stutter or not. Her approach to understanding and supporting sensitive nervous systems offers a revolutionary perspective that could change how you see and support your child. Grab your free ticket for the summit here.

Comments